In patients with essentially normal lung tissue, acute respiratory failure (ARF) usually means a partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2) greater than 50 mm Hg and a partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) less than 50 mm Hg. These limits, however, don't apply to patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), who commonly have a consistently high PaCO2 and low PaO2. In COPD patients, ARF is indicated only by acute deterioration in arterial blood gas (ABG) levels an corresponding clinical deterioration.

In patients with essentially normal lung tissue, acute respiratory failure (ARF) usually means a partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2) greater than 50 mm Hg and a partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) less than 50 mm Hg. These limits, however, don't apply to patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), who commonly have a consistently high PaCO2 and low PaO2. In COPD patients, ARF is indicated only by acute deterioration in arterial blood gas (ABG) levels an corresponding clinical deterioration. Causes

- Airway irritants--smoke or fumes

- Any condition that increases the work of breathing and decreases the respiratory drive of patients with COPD

- Chest trauma

- Head trauma

- Heart failure

- Injudicious use of sedatives, opioids, tranquilizers, or oxygen

- Metabolic acidosis

- Myocardial infarction

- Myxedema

- Pneumothorax

- Pulmonary emboli

- Thoracic or abdominal surgery

Signs and symptoms

- Increased, decreased, or normal respiratory rate, depending on the cause; shallow or deep respirations, or respirations that alternate between the two; and air hunger

- Cyanosis of the oral mucosa, lips, and nail beds possible, depending on the hemoglobin (Hb) level and arterial oxygenation

- Crackles, rhonchi, wheezes, or diminished breath sounds

- Restlessness, confusion, loss of concentration, irritability, tremulousness, diminished tendon reflexes, and papilledema; possible coma

- Tachycardia, with increased cardiac output cardiac output and mildly elevated blood pressure (occurs early in response to a low PaO2)

- Arrhythmias

- Pulmonary hypertension

- Accessory muscle use

- Tachypnea

- Cold, clammy skin

Diagnostic tests

- Pulse oximetry may show decreased arterial oxygen saturation.

- ABG analysis reveals hypercapnia and hypoxemia; bicarbonate levels are increased, indicating metabolic compensation for chronic respiratory acidosis.

- Hb levels and hematocrit are abnormally low, possibly due to blood loss, indicating decreased oxygen-carrying capacity.

- Serum electrolyte levels may indicate hypokalemia, which may result from compensatory hyperventilation--an attempt to correct alalosis; hypochloremia is common with metabolic alkalosis.

- White blood cell count is elevated if ARF is due to bacterial infection; in certain cases of profound septicemia, the leukocyte count may be decreased.

- Gram stain and sputum culture results can identify pathogens.

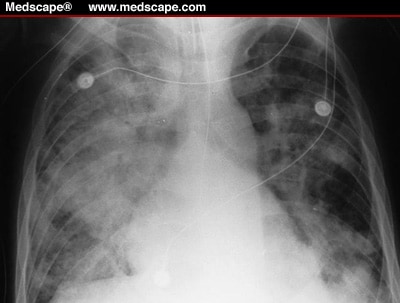

- Chest X-rays reveal pulmonary pathology, such as emphysema, atelectasis, lesions, pneuothorax, infiltrates, or effusions.

- Electrocardiography reveals arrhythmias, which commonly suggest cor pulmonale and myocardial hypoxia. Large P waves ("p pulmonale") may indicate a history of right-sided heart failure.

Treatment

- Oxygen therapy using nasal prongs or a Venturi mask to raise the patient's PaO2 (if the patient has COPD) is used cautiously to promote oxygenation.

- Bidirectional positive-pressure airway mask is used over the oronasal region or mechanical ventilation through an endotracheal or a tracheostomy tube is oredered (if significant respiratory acidosis persists).

- High-frequency ventilation is intituted (if the patient doesn't respond to conventional mechanical ventilation.)

- Antibiotics are prescribed for infection.

- Bronchodilator is used to maintain airway patency.

- Anxiolytic is ordered to promote relaxation and reduce anxiety.

- Corticosteroids are prescribed to decrease inflammation.

- Histamine-receptor anatgonist may be ordered to prevent ulcer formation.

Nursing considerations

- Assess the patient's respiratory status frequently (pulse oximetry, breath sounds, and ABG results) and report changes immediately.

- Give enough oxygen to maintain a PaO2 of at least 50 to 60 mm Hg. Patients with COPD usually require only small amounts of supplemental oxygen.

- Maintain a patent airway. If the patient is retaining carbon dioxide, encourage him to cough and to breathe deeply with pursed lips.

- If the patient is alert, have him use an incentive spirometer.

- Keep the head of the bed elevated to at least 30 degrees.

- If the patient is intubated and lethargic, turn him every 1 to 2 hours.

- Use postural drainage and chest physiotherapy to help clear the patient's secretions.

- Monitor and record serum electrolyte levels carefully, and correct imbalances; patient's intake and output or daily weight.

- Monitor the patient for cardiac arrhythmias.

- Give prescribed medications.

For mechanical ventillation

- Check ventilator settings, cuff pressures, and ABG values frequently because the fraction of inspired oxygen (FIO2) setting depends on ABG levels. Draw a blood sample for ABG analysis 20 to 30 minutes after every FIO2 change, or check ABG levels with oximetry, as ordered.

- Change ventilator circuits every 24 to 48 hours, per your facility's policy.

- Suction the trachea, after hyperoxygenation, as needed. Observe for a change in the quantity, consistency, or color of secretions. Provide humidification to liquefy the secretions.

- Keep the nasotracheal tube midline within the nostrils, and provide good hygiene. Loosen tape periodically to prevent skin breakdown. Avoid excessive movement of any tubes, and make sure the ventilator tubing is adequately supported.

- Provide an alternate means of communication.

- Provide emotional support to the patient and family.