A form of pulmonary edema that causes acute respiratory failure, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) results from increased permeability of the alveolocapillary membrane. Fluid accumulates in the lung interstitium, alveolar spaces, and small airways, causing the lung to stiffen. This stiffening impairs ventilation, prohibiting adequate oxygenation of pulmonary capillary blood. Severe ARDS can cause intractable and fatal hypoxemia, but patients who recover may have little or no permanent lung damage.

Pathophysiology of ARDS

Causes

- Aspiration of gastric contents

- Cardiopulmonary bypass

- Drug overdose (barbiturates, glutethimide, opioids) or blood transfusion

- Microemboli (fat or air emboli or disseminated intravascular coagulation)

- Near drowning

- Oxygen toxicity

- Pancreatitis

- Sepsis (primarily gram-negative)

- Smoke or chemical inhalation (nitrous oxide, chlorine, ammonia)

- Trauma (lung contusion, head injury, long bone fracture with fat emboli)

- Viral, bacterial, or fungal pneumonia

Signs and symptoms

Early

- Rapid, shallow breathing and dyspnea (within hours to days of the initial injury)

- Intercostal and suprasternal retractions

- Crackles and rhonchi on auscultation

- Hypoxemia causes restlessness, apprehension, mental sluggishness, motor dysfunction, and tachycardia

Late

- Overwhelming hypoxemia

- Hypotension

- Decreased urine output

- Respiratory and metabolic acidosis

- Ventricular fibrillation or standstill

Diagnostic tests

- Arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis first shows a decreased partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2)---less than 60 mm Hg---and a decreased partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2)---less than 35 mm Hg. pH ussually shows respiratory alkalosis. As ARDS becomes more severe, ABG levels indicate respiratory acidosis (a PaCO2 greater than 45 mm Hg) and metabolic acidosis (a bicarbonate level less than 22 mEq/L) aswee as decreasing PaO2, despite oxygen therapy.

- Pulmonary artery (PA) catheterization helps identify the cause of pulmonary edema by allowing evaluation of pulmonary artery wedge pressure (PAWP) (normal PAWP values in ARDS 12 mm Hg or less) and collection of PA blood (shows decreased oxygen saturation, indicating tissue hypoxia).

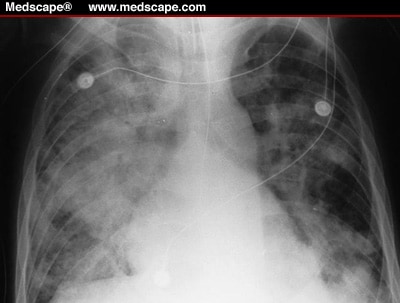

- Serial chest X-rays initially show bilateral infiltrates; in lter stages, the X-rays show ground-glass appearance and, eventually (as hypoxemia becomes irreversible), "whiteouts" of both lung fields.

- Gram stain and sputum culture and sensitivity test results show infectious organism (if infection is the cause).

- Blood cultures reveal the infectious organism.

- Serum amylase levels increase if the patient has underlying pancreatitis.

- Toxicology test identifies the drug ingested in ARDS caused by a drug overdose.

Treatment

- Treatment of the underlying cause is started.

- Humidified oxygen is given through a tight-fitting mask, which allows for the use of continuous positive airway pressure.

- For hypoxemia that doesn't respond adequately to this treatment, the following may be ordered: ventilatory support with intubation, volume ventilation, and positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP); pressure-controlled inverse ratio ventilation to reverse the conventional inspiration-to-expiration ratio and minimize the risk of barotrauma.

- When a patient with ARDS needs mechanical ventilation, an opioid, sedative, or neuromuscular blocker may be ordered to ease ventilation and decrease oxygen consumption.

- High-dose steroids may be prescribed for ARDS caused by fat emboli or chemical injury.

- Diuretics are oredered.

- Correction of electrolyte and acid-base abnormalitiesis oredered.

- I.V. fluids and a vasopressor may be needed to maintain blood pressure.

- Antimicrobial is prescribed if the patient has a treatable infection.

Nursing Considerations

- Frequently assess the the patient's respiratory status. Be alert for retractions on insporation. Note rate, rhythm, and depth of respirations, and watch for dyspnea and the use of accessory muscles of respiration. On auscultation, listen for adventitious or diminished breath sounds. Check for clear, frothy sputum that may indicate pulmonary edema.

- Observe and document the patient's neurologic status, including level of consciousness and mental sluggishness.

- Maintain a patent airway by suctioning, using sterile, nontraumatic technique. Ensure adequate humidification to help liquefy tenacious secretions.

- Closely monitor heart rate and blood pressure. Watch for arrhythmias that may result from hypoxemia, acid-base disturbances, or electrolyte imbalance.

- GIve medications as prescribed.

- With PA catheterization, know the desired PAWP level. Watch for decreasing mixed venous oxygen saturation.

- Monitor serum electrolyte levels, and report any imbalances immediately. Measure intake and output, and weigh the patient daily.

- Check ventilator settings frequently. Monitor ABG levels; check for metabolic and respiratory acidosis and PaO2 changes.

- If the patient has severe hypoxemia, he may need controlled mechanical ventilation with PEEP and inverse ratio ventilation. Give sedatives, as needed, to reduce restlessness.

- Because PEEP may decrease cardiac output, check for hypotension, tachycardia, and decreased urine output. Suction only as needed to maintain PEEP.

- Reposition the patient frequently, and note any increase in secretions, temperature, or hypotension, which may indicate a deteriorating condition.

- Accurately record caloric intake. Give tube feedings and parenteral nutrition, if required.

- Perform passive range-of-motion exercises, or help the patient perform active exercises, if possible. Provide meticulous skin care. Allow periods of uninterrupted sleep.

- Provide the patient and his family with emotional support.

0 comments:

Post a Comment